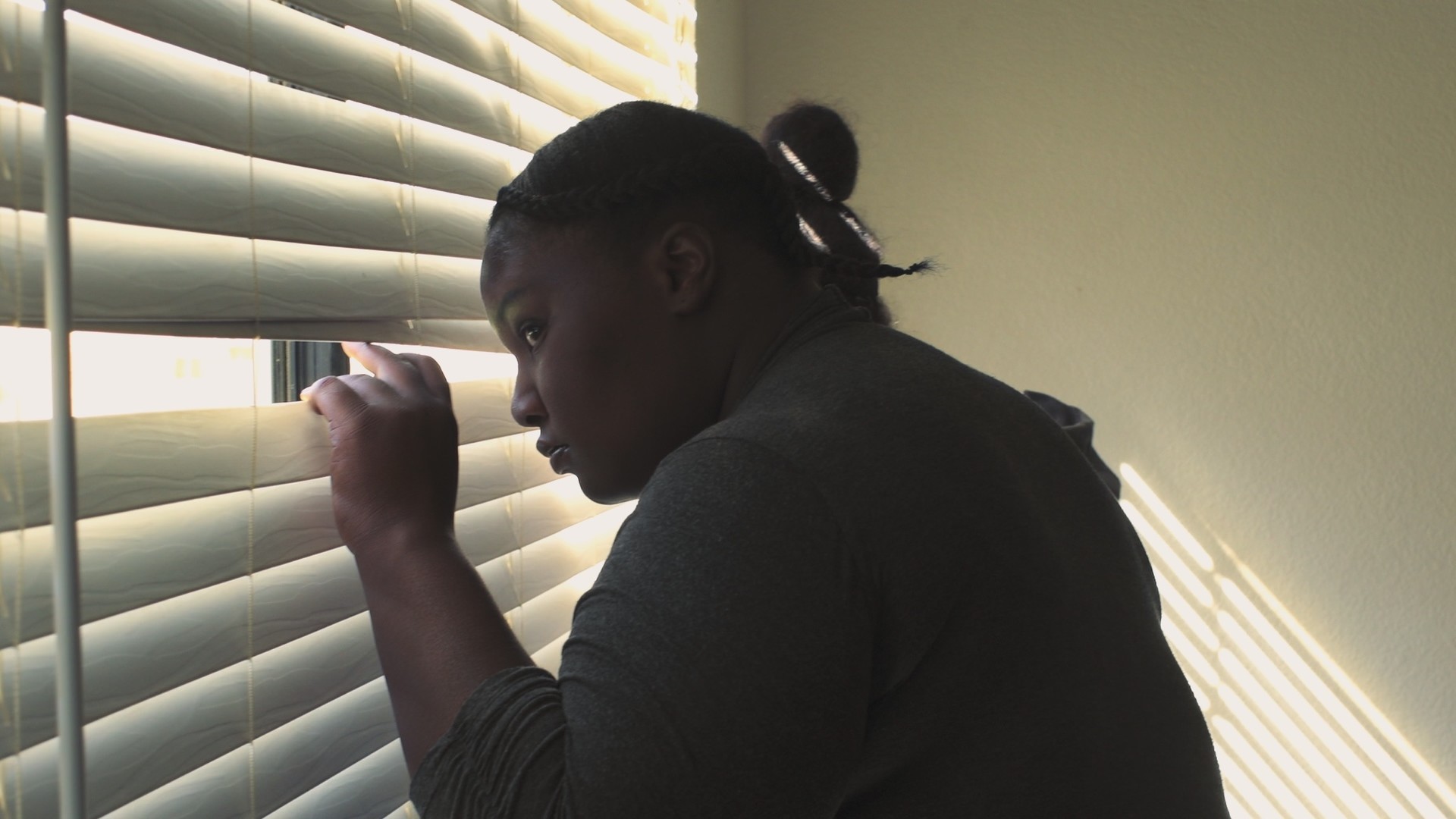

We are in an empty house. Through window blinds, bright sunlight dances on walls and makes shifting reflections.

Our eyes pan across the grainy white walls.

Their expansive blankness turns the vacated house into an abstract shadow (Isabelle Tollenaere,The Fruit Tree, 2022).

We are sleepwalking in a stranger’s daydream.

LSFF 2024’s documentary programme ‘The house shelters daydreaming’ invites us into deserted houses. Borrowing its title from Gaston Bachelard’s book The Poetics of Space, the screening features films that meditate on messages conveyed by real, virtual, or metaphoric houses.

Many of these houses are homes once inhabited and later abandoned for different reasons. In the empty sunlit house in Tollenaere’s The Fruit Tree, we stumble across buried memories about a childhood home as we join two young women in viewing a property. From a window of the house on offer, we watch the pale midday sky turn golden, mauve, blue, and pitch-dark. Lights in the distance twinkle like stars. One of the two women talks about her long-gone childhood home and the fruit trees outside its window.

Made home and then given up, houses bear hope, nostalgia, and pain. They are what has to be left behind when relocation – voluntary or not – takes place in response to changed conditions of living. We roam Moscow and enter flats left behind by their owners on the brink of the still ongoing Russo-Ukrainian War (Zhenia Kazankina, Empty Rooms, 2022). Unmade beds, half emptied book shelves, a favourite portrait, a Botticelli painting that hasn’t been hung yet.

‘I wasn’t going to leave it. I didn’t want to leave it,’ a flat’s old occupant tells us. Beloved possessions are in their usual place in the houses, but the dreams about making a home – a place that promises to shelter and comfort – they once carried are lost. Silent and still, deserted houses are a witness of both intimate agonies and collective traumas.

In ‘The house shelters daydreaming’, houses are unstable containers. Repeatedly, films featured by the screening direct our eyes towards the strange moments when houses fail to confine, hide, or protect. In Xinyu XuXX’s The Room it Leaks (2023), a leaking house is one’s body, a mother’s womb, and a room that is both a sanctuary and a prison.

It is a metaphor for things that cannot keep inside the painful contradictions they cause. A dog in Igor Grubic’s Ingresso Animali Vivi (2023) leads us deeper and deeper into the dreamscape of a slaughterhouse, passing through cold, sterilised halls, following the invisible but unconcealable traces left by slaughtered animals. Walls disappear as we adopt a nonhuman point of view (the dog’s?), and the slaughterhouse become a transparent death camp from which the scent of brutality leaks wildly.

Mobility and captivity are entwined ironically in the house.

Exploring the intimate poetics of the house, ‘The house shelters daydreaming’ reconsiders the essence of documentary films and asks what it means to ‘document’. Both The Room it Leaks and Asli Baykal’s DARKROOM (2022) play with photographic documents. Fracturing and layering images from family archives, The Room it Leaks’s digital and physical collages rewrite the protagonist’s childhood so that present and future acts of resistance become possible.

DARKROOM interrogates the meaning of documenting even more directly. We follow a group of children around at an after-school photography workshop in Mardin, a Turkish city by the borders of Syria and Iraq. They take photos, develop films, and look for their own faces on negative sheets. A boy points his red camera at us for a short moment. Who’s documenting whom?

Many of the workshop’s young participants are from conflict zones nearby. Sheltered from the barren landscape by the darkroom, they snuggle together under the dim safelights and talk about the photos they will take one day. Like Moscow’s abandoned flats that once brimmed with hope, or the sunny room with a view of fruit trees, the darkroom is an intimate house in which the minute traces left by large things – history, politics, society – can be found and felt. Entering this house, documentary films become secret daydreams.